Don’t worry about that title.

I’m a capitalist, down to the bone, blood, and sinew. During basketball games, as a 6’2″ 9th grader, I sat on the bench reading books about the stock market. These days, I spend almost all of my spare mental time wondering how I can make my small business grow, since I have six children and lots of nephews and nieces who enjoy the family business. I believe, with Ronald Reagan, that the best way to help the poor is to give them a job, because when you get right down to it, Barack Obama doesn’t create any real jobs; he only passes out the wealth created by Home Depot, Boeing, Delta Airlines, and that machine shop across the freeway that employs 10 families.

Moreover, I believe God loves a good capitalist too — certainly a lot more than an unaccountable DMV slug, who gets paid whether they smile at the “customers” or not. Nothing is quite so infuriating, to God and man, as the civil servant who sees his own generously-compensated work as ennobling, while that of the private sector as too “commercial,” or too “make-a-buck.” So don’t get me wrong. I respect private property, the profit motive, and the right to make a buck. I eat all of that for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

But, really, what good is money if you live at the North Pole? Can you really live very large in a place where you can’t buy fresh bagels? Years ago, some friends of ours returned from living in Turkey, and even though they were paid well, they complained about the potato chips: they were always rancid. In a very real sense, you are only as wealthy as the nearest grocery store.

For our new web-television series, Primary History, I was pondering it all in terms of an English shilling. In period literature and movies, I’ve seen that term — shilling — over and over, and I got to wondering: what was a shilling worth? What could a “farthing” buy you? How wealthy would a “guinea” in your pocket make you?

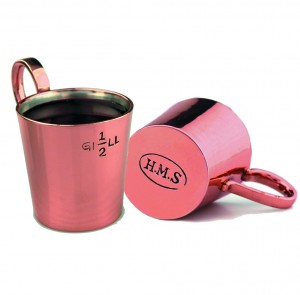

I won’t bother you with too much of the math, but here are the basics. John Adams observed, in his journal, that an old man purchased a “gill” (four ounces) of West India Rum for “two shillings, four pence” in the year 1754. In 2015, you can purchase 25 ounces of West India Rum for $22.00.

Now you might be tempted to make it a matter of simple conversion, assuming the value of rum as a constant. If four ounces of rum then cost 2.33 shillings, then 100 ounces would cost 58.25 shillings, (25 x 2.33). Today, you can buy 100 ounces of Rum for $88, (4 x $22). By that logic, 58.25 shillings equals $88, so a shilling would be worth about $1.50 ($88/58.25).

But wait a minute. How long did it take a common man in the 18th century to earn a shilling? According to one source, the average day laborer in the mid 18th century earned about 2 shillings, 10 pence a day. In those days, a shilling was 12 pence, so that meant 2.83 shillings a day. In 2015, the federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour, or, assuming an 8 hour work day, about $58 a day. By this reckoning, a shilling would be worth about $20 of our dollars, ($58/2.83 shillings).

So is a shilling worth about $1.50 or $20?

Let’s put the rum and the labor together: in 2015, you can purchase an ounce of rum for $0.88, ($22/25 oz). One of today’s minimum wage workers, in other words, can purchase 8.2 ounces of rum with one hour of work, ($7.25/$0.88). In 1754, an ounce of rum cost 0.58 shillings (2.33 shillings/4 ounces). One hour of labor, in 1754, would purchase 0.6 ounces of rum (0.35 shillings an hour / 0.58 shillings an ounce). That’s being generous and assuming an 8 hour work day. Extending this out, one of today’s workers can buy 65 ounces of rum a day with his labor (more than a half gallon), and a day laborer in 1754 could purchase 4.8 ounces of rum (0.6 ounces x 8 hours). Today’s entry-level workers, in terms of West India Rum, are 13.5 times more wealthy than the day laborers of 1754. Put in a day of work now and you get a half gallon of rum, as compared to the 5 shots of yesteryear.

With some obvious exceptions made for better tools and conditions, a day of work in the 18th century probably “feels” something like a day of work in the 20th century, but it obviously buys you less. A shilling is much closer to being about $20 if you consider how many shillings it takes you to buy the things you buy today, and that’s because if we just use rum as a guide, there’s a lot more of it around; it’s cheaper to produce, cheaper to ship, cheaper to store, cheaper to retail, cheaper to transact, and so all of that means a day of our labor buys more than it did in the 18th century. The presence of more wealth (as defined purely by stores of rum in this case), makes our life easier. The village today has more plentiful rum, and so we devote less of our labor to earn it. Conversely, when the village has very little rum, we work harder, and longer hours, to get it.

And that brings me back to my thesis; we’re only as wealthy as what we collectively produce. If I have a warehouse full of gold bricks, but no one is producing any food, I’m desperately poor. If I have a palatial home, but no one, for three thousand miles knows how to produce window panes, eventually the home will be a ruin, as the elements take over. If I have a cargo van full of one hundred dollar bills, but literally all of life’s bare necessities — clothing, grain, meat, medical supplies — are gone, I might as well use the cash to start a fire.

The principle is broader, too, than just material wealth. What good is writing literature if no one is capable of reading it? How fun is your “finer things” club, if no one drinks tea? How safe is your posh Dubai country club, if it is surrounded by ISIS warriors on jihad crack?

Like it or not, wealth can only really be measured by the cultural and economic strength of those who surround you; you can only sell so many sports cars in Haiti.

In truth, of course, history tells us that we gravitate towards a position just short of the extremes I’ve painted here. The King’s gold is never rendered entirely useless, because peasants will endure keeping one bushel of wheat to stay alive, even if it means giving nine to the king as tribute. In Soviet Russia, while common laborers starved, the Communist party brass enjoyed their dachas and Black Sea caviar.

But the glory that is America — a million kids with a better idea for a virtual reality game, a million couples dreaming of owning their own vineyard — lies in the creation of broader wealth through an individual desire to grow rich by doing it better. Americans aren’t just working to survive; we are working to get rich, and by getting rich, even if we don’t quite get there, we make the rest of the place and the people better and richer. Even if we didn’t create the chain of 100 restaurants, we employed 300 people building two of them.

I know how this works. I once made very good money programming computers, but it wasn’t just my desire to program computers that earned me the money. I couldn’t sell IT services to impoverished Cuban farmers, left destitute by socialism. I was able to bill a lot for my time, because my customers were very successful. And my story has played out, in American history, on a much broader and grander scale. We are rich, because we encourage others to be rich. It’s self-interest and collective interest at the same time.

The easier way, the way that attracts demagogues since the beginning of time, is just to steal it, tax it, and redistribute it, but that way leads to empty shelves, cold, hard bitter labor, and a few strong man thugs at the top, enjoying the dachas and the caviar. If we aren’t sure we can keep our money, if we believe a new round of politicians will tax it all away, we stop working for it. We settle for one bushel of wheat, and survival — instead of the 80 hour weeks, the risk, and the innovation that makes the rum cheap for everyone.

And to answer the question…

A farthing (1/4 of a penny) … $0.43 today

A penny … $1.72 today

Tuppence (two pennies) .. $3.44 today

A Shilling … $20.58 today

A Pound (20 shillings) .. $411.60 today

A Guinea (21 shillings) .. $432.18

A substantial English gentleman with

a fortune of 5,000 a year… $2,058,000 a year