Ever since Sam Kinison used the term “courtesy laugh,” I’ve been careful to keep track of films that actually deliver at least a little honest comedy, and while Theodore Melfi’s St. Vincent isn’t fall on the floor stuff, there’s something sweet and honest about the thing. In the grumpy-old-man, get-off-my-lawn category this delivers.

Ever since Sam Kinison used the term “courtesy laugh,” I’ve been careful to keep track of films that actually deliver at least a little honest comedy, and while Theodore Melfi’s St. Vincent isn’t fall on the floor stuff, there’s something sweet and honest about the thing. In the grumpy-old-man, get-off-my-lawn category this delivers.

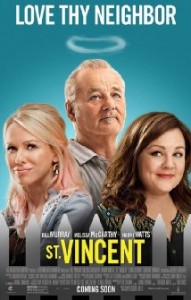

I find myself a bit surprised by that because almost everything about the story pre-announces the conclusion. You see it all coming — the runty kid named Oliver (Jaeden Lieberher) who will be taught how to fight, after a predictable period of vulgar indifference by the dissipated Vietnam Vet Vince (Murray), the bookie who will eventually collect a debt, the Russian pole dancer/call girl “Daka” (Naomi Watts) who will eventually reveal her golden heart, the resilient single mom Maggie (Melissa McCarthy) who will make a new life after being cheated on. There really is nothing new under the sun; King Solomon was right about this sort of thing.

You might call it a textbook example of good writing and gifted performers pitching in to sing a song you’ve heard many times before in a way that surprises, and blesses you. Chris O’Dowd, playing Brother Geragty brings a nutty, no-nonsense, spiritually-pluralistic twist to the Catholic classroom. He has gentle contempt for his young charges, doesn’t expect anything from them, and still appears to love them. Maggie isn’t just a generic health care worker. She’s one of those CT scan techs, who knows when people have tumors, but can’t say anything about it to the patient. McCarthy recounts this burden, along with a hilarious sad inventory of her ex-husband’s close-to-home infidelities in a way that leaves you chuckling, compassionately, through her tears. And “Daka” isn’t just any pole dancer; she’s a pole dancer with a baby-bump, who can’t seem to right herself. (Talk about removing the mystery.) I found myself admiring Naomi Watts for being willing to present her wrinkles and bumps in a way that seems a bit self-sacrificial for a beauty like hers.

And then there’s the Bill Murray show, which, like the Jack Nicholson show before it, seems to be about utterly credible irreverence, lack of pretense, and lovable rudeness. The twist here, (the film’s hook) is that he gets to play a careless caretaker, who takes a child to race tracks and strip bars because he’s out of money and he needs the hourly baby-sitting wage. In one scene he watches his young charge take a beating, and he steps in for protection–and you get the sense it’s more about having contempt for the young slugs than it is about doing his job. To the attackers, paraphrasing, says Murray: “You’re Mara’s kid, aren’t you? Of course you are. You’re the only Puerto Rican Polack in Brooklyn. Get out of here.” He breaks their skateboard. He teaches the kid to fight. He drinks. He gambles. He never cleans up what he doesn’t have to. His dissipation is as epic as his demands are unrealistic. He’s a wreck who defies anyone to explain to him exactly why he’s a wreck.

But, of course, underneath all of that, he has a heart. He was a war hero and a caring husband and a man who at least knows, keenly, his own failings. Our young hero, Oliver, manages to dig beneath the obvious shortcomings to discover Vincent’s history, and in the school auditorium, as the common saints we see all around us are announced to the world, Vincent isn’t ignored.

“Yep,” I said to myself, wiping away the tears and actually catching my breath, “this works.”

The story tells us what we already know: we really do ache to know, and love, our neighbors.