The most effective response to terror on 9-11 came from the regular folk, the “let’s roll” citizens of flight 93. To get America back, we need less faith in the professionals.

In the summer of 1769 the town of Boxford, Massachusetts was on edge. Jonathan Ames’ pretty young wife, Ruth, had taken ill, and when Mrs. Kimball, a neighbor, came to visit, Ruth’s mother-in-law claimed the odor coming from her chamber was too foul to admit visitors. Kimball nevertheless insisting on a visit, found the room agreeable, but her friend writhing in pain on the bed and foaming at the mouth. When the young woman died the next day, her body was buried quickly, attended by an out of town minister for a very small group of family, with no coroner examining her remains.

In the summer of 1769 the town of Boxford, Massachusetts was on edge. Jonathan Ames’ pretty young wife, Ruth, had taken ill, and when Mrs. Kimball, a neighbor, came to visit, Ruth’s mother-in-law claimed the odor coming from her chamber was too foul to admit visitors. Kimball nevertheless insisting on a visit, found the room agreeable, but her friend writhing in pain on the bed and foaming at the mouth. When the young woman died the next day, her body was buried quickly, attended by an out of town minister for a very small group of family, with no coroner examining her remains.

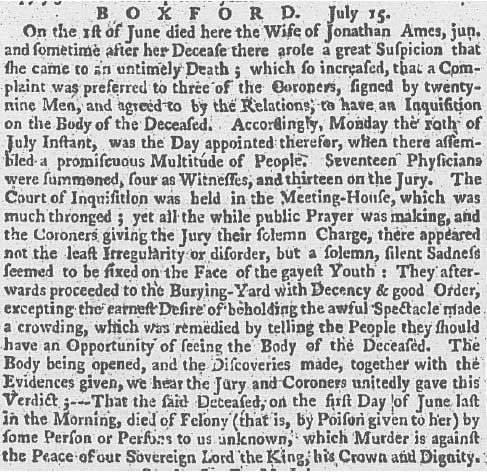

Within days, the town was demanding an investigation, and a formal accounting that by our standards would seem ghoulish. Gathering at the meeting house, after prayer, a jury of 25 citizens, 13 of whom were physicians, ordered the body to be exhumed, not just for the members of the medical profession, but for the whole town to see.

The crowd was so immense, and the desire to see the corpse so widely shared, they had to be assured by the authorities they would all have a chance to see the body. The jury, after examination, suspected foul play, and the case proceeded to trial, on the theory that Ruth was poisoned, by either her husband or her mother-in-law, both of whom were defended by a 34 year old John Adams. (By the way, you can hear your sleepy early morning correspondent discuss all things colonial on Tuesday mornings with Rich Girard of New Hampshire Family radio.)

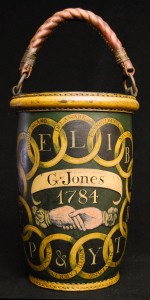

Like most 18th century New England realities, government was a shared, largely amateur obligation. Constables, the antecedent of today’s police force, were elected at town meetings. (By all accounts, the task of arresting neighbors was not very popular.) Fire fighting was volunteer, but came with heavy penalties for not participating, and not being ready with the proper number of working, leather fire buckets. The community built roads together, fought together, and prayed together, where the “meeting house” served as a place to pray and argue law within the same confines. As we see in the murder of Ruth Ames, the public apparently felt entitled to examine the body of the alleged victim. If a murderer was on the loose in your town, you had a right to examine the evidence yourself.

We tell ourselves that was all more than two hundred years ago. We are now deeply entrenched in the era of specialization. Forensic investigation is now sifting evidence at the molecular level and even road construction requires extensive data on soil compaction and environmental impact. You haven’t had SWAT team training, and you certainly will not assist the police in a criminal investigation, unless you’re a “person of interest” that is.

Move on folks. Let the professionals do their job.

I can’t help thinking of my dad’s experience of the Navy in World War II. He told stories of bankers, engineers, lawyers, and insurance salesmen all volunteering to help the “professional army” get the job done quickly. And they did after all. They managed to subdue two military giants — Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany — in a little more than 44 months. By comparison, our modern, highly technical, highly “professional” armed services get mired in procedural police actions that smoulder on for years, if not decades, without any resolution, much less the civilization building that took place in Japan and Germany. To be fair, our politicians are a lot more girlish and cautious these days, and far more willing to apologize for American values, but I can’t help wondering if America — and the modern world in general — has become far too professional, and far too addicted to conventional, but peer approved, failure.

I can remember thinking on the morning of September 11, 2001, “don’t we have a civil air defense capable of scrambling fighters to protect our cities?” Today, with the endless TSA screening, I still wonder why we make all American travelers potential criminals instead of circling our major cities with anti-jihad technology, but who am I to question? I’m just a guy who loves colonial history and common sense. There’s no question that training and expertise have their place, but that training and expertise — the official kind — was not there on 911. The single most effective response to professional jihad on that day was the amateur bravery of regular American citizens on flight 93 — the folks who stormed the cockpit, totally without training. They wrestled that plane to the ground and likely saved it from reaching its target.

The story is old and biblical. Little David does it his way against the giant. “God resists the proud, but gives grace to the humble.” We know all of that, but — my word — we are paying these policemen, these academics, these engineers so much, shouldn’t we defer to them when a crisis looms?

Perhaps, but the urge to protect the public from information, the urge to call the 1769 citizens of Boxford positively medieval in their public crime investigation, can be counterproductive. If anything, police body cams these days, almost always end up vindicating the police, and when they don’t, they help us identify the rogues. What procedural, legal prejudice against the public prompted North Carolina to statutorily keep information from public view in the shooting death of Keith Lamont Scott? Why shouldn’t the taxpayers be able to see the video information recorded by their own officers while on duty? How have we allowed ourselves to defer to “professional expertise,” when, after all, we’re the ones paying for that expertise?

As with any of our freedoms, there is always a collision of rights involved. Theoretically, a jury might be prejudiced by too much crime scene information being made public too soon, and the right to a fair trial might be infringed, but isn’t that a pretty bald-faced show of contempt for the public in the first place? I can’t know too much, because I may not be able to accept the controlled flow of evidence you may wish to show me, as a juror, four months from now?

In the North Carolina case, a murderous, looting riot boiled over — fueled by a public without the sort of first hand evidence that may have cooled their passion, or perhaps rendered their cause less worthy. And if their cause was worthy, whatever happened to “following the truth where it leads us?” Is that an objective only allowed to professionals, behind closed doors, away from the unwashed eyes of the amateurs?

This election season, the elites have decided Hillary Clinton is the credentialed expert and Donald Trump is the outside amateur, but, try as we may to make a charitable conclusion, Yale Law school hasn’t made Hillary much of a success. Her dabbling in foreign policy has literally killed thousands of people in the middle east and fueled the ISIS quagmire into a set of conditions that may well lead to another world war. Her stable of “experts” have put Iran well on the way to nuclear weapons — a disaster the slowest kid in the class could have warned her against. She’s cautious, imperial, well trained, credentialed — and thoroughly incompetent.

This election year, we should restore an ancient American tradition — the wisdom of amateurs.