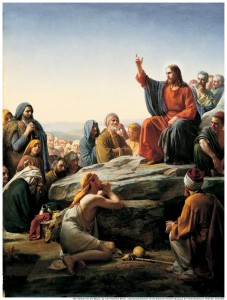

I will confess to being both pleasantly charmed and puzzled by the Sermon on the Mount. As I wrote yesterday, the Savior’s words in Matthew 5:48, (“Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father, which is in heaven, is perfect”), should make an honest student of Christ scratch his head. Perfect? Perfect as God? How’s that again? Can we just back up a moment and talk about that?

I will confess to being both pleasantly charmed and puzzled by the Sermon on the Mount. As I wrote yesterday, the Savior’s words in Matthew 5:48, (“Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father, which is in heaven, is perfect”), should make an honest student of Christ scratch his head. Perfect? Perfect as God? How’s that again? Can we just back up a moment and talk about that?

Many never have a talk with God about that, and I’m convinced that entire branches of the faith, and some secular heresies, such as Communism, have foundered because their understanding of these words are superficial, and very selective.

One very popular Baptist teacher recently wondered why the church, for example, wasn’t more brokenhearted and poor in spirit. (Matthew 5:3-4) He seemed to be teaching that you should seek to be miserable, seek to be poor, so that Jesus would comfort you. You hear a version of this when a missionary returns from some poverty-stricken country, and he then wishes poverty on you, so that you might pray with the fervor of the oppressed. That strikes me as particularly backward. Jesus tells us to pray for our daily bread. Persecution may come for telling the truth, but we don’t pray for the persecution or the misery itself. We may count it all joy, but we don’t ape the poor to beg God’s consolation. We feed the poor. We teach them how to work. We share advances in western technology made possible by God’s hand, but we shouldn’t be starting little Christian poverty clubs, anymore than we would jump off the parapet of the temple to tempt God’s blessings.

It seems fairly clear that verses 17-48 in Matthew 5 are spoken in service of one primary teaching reality: we are very far from God’s standard. His law stands. It will remain until “heaven and earth pass away,” and if you don’t teach the law, you are “the least in the Kingdom of Heaven.” Look at a woman the wrong way and you have committed adultery with her, (verse 28). Marry a woman who was abandoned by her previous husband? You are both in adultery, (verse 31). Never swear an oath? (verses 34-35) Cut off your hands and gouge out your eyes if they cause you to sin? (verses 29-30). Loan to anyone who asks you, whatever they want, whenever they want it? (verse 42). Submit to beatings? (verse 39) Love and pray for your enemies? (verse 44). Finally, be as perfect as God? (verse 48).

There are those in the church who have turned all of this into a kind of behavioral code of conduct. I have encountered Christian pacifists, for example, who swear up and down that if their home were invaded by violent men, and their wives and daughters were raped, they wouldn’t lift a hand to protect them. Some Christian denominations have refused to take oaths. Still others, as in the case of the Shakers, took sexual purity so seriously, they taught church wide celibacy. (This makes for great furniture but dwindling congregations and wild interpretive dance.) The contemporary Roman Catholic church preaches against the death penalty, and mercy for those condemned by the civil magistrate. Some Utopian Christian communities, and Christian heresies, like Marxism, have taught a kind of common purse, as though a society could actually flourish with no respect for private property, and no accountability for its use. I have encountered pietistic home school families who teach that young couples shouldn’t even hold hands, until they take their actual wedding vows, in what seems (to me) a forlorn, ridiculous attempt to match God’s perfection and holiness.

I haven’t yet met a congregation of believers who have sawed off their hands and gouged out their eyes — which may speak to the particularity of those who see a specific code of conduct in the Sermon on the Mount: even those who regard it as a “rule for living,” can only abide the parts they think they can manage.

Some recoil at the notion that Jesus was resorting to hyperbole, here, so as to prove our need for a savior. They see such an interpretation as an attempt to skirt the law, but I have to wonder: do they see Jesus as a literal “vine,” (John 15) or a literal “door” (John 10)? Do they ignore the “explicit mystery” of His teaching, where He seems to imply that only those who are hungry enough to reach through His words, to struggle with His doctrine, are worthy of Him? He speaks in riddles and parables, and He purposely declared some were intended never to understand them. (Matthew 13: 11-15) Is it so impossible to believe that a chapter ending with a command to be as perfect as God, is, in fact, an invitation to pause and reflect and ask a few questions? A wink from the Master? Or was God really asking you to cut off your hand?

You have to ask yourself a few questions: if the Sermon on the Mount is the sum total of the gospel, how do you justify the Christian banker sitting next to you in church? The Christian marine? The Christian police officer? How do you justify locking up a man in jail for decades, or executing him? Have two thousand years of the church, and the many civilizations based on Christ’s teachings, been absolutely wrong-headed? Was every Christian father who protected his wife and children against invading Norsemen and Saracens a gross heretic? Were you wrong not to give $500 to your brother hooked on heroine? When someone stole your car, were you wrong to file a police report?

Some would say these questions judge the gospel by the culture, and not the culture by the gospel, but only, again, if we insist on declaring single passages as sovereign gods, to which we can build our preferred idol. It’s a startling image, the Bible not taken as an entirety, but broken up into a pantheon of separate deities, each with their own disciples. Are you a coward? Worship “love your enemies.” A prude? Worship “adultery in your heart.” A Marxist? Worship “do not turn away the one who wants to borrow.” The Sermon on the Mount, without Romans 13, and the appropriate boundaries of judgment and mercy, can descend into an idolatry.

And, yet, there is still a charming mystery in the Sermon on the Mount, because I believe, strangely, it is both ridiculous hyperbole and beautiful perfection at the same time. To us, having only the smallest sliver of God’s nature and authority, we can only scoff at lending to anyone who asks. First of all, we don’t own the cattle on a thousand hills. Our resources are limited. God, however, could drop $500 in the hand of a heroine addict for the purposes of testing, and curing him, and there would be no reduction in God’s account. He can endure entire generations of gross evil, because He sits on the throne. If you have ever been in executive authority, and you have final say in any organization, you may have experienced this insight into the “mercy” authority makes possible. When you were pulled over in traffic, you may panic at the officer’s authority, but if you’ve been that officer, you know you can offer mercy, because you can also offer judgment at any time as well.

And that may speak powerfully to how Jesus concluded that first chapter in the greatest sermon of all time. In asking us to be as “perfect” as God, he was inviting us to know the whole truth, and not just the part that pleases us, to hold both judgment and mercy in our hands, to know when to make peace, and when to make war.